| Intro | |

| What is Intelligence? How Do We Use Intelligence? What Value is Intelligence? What Recommendations Stem from Intelligence? | |

| So where does this leave us? | |

| What is Intelligence? | |||||

There are a number of ways to conceptualize what intelligence is. Here's seven we'll discuss:

1) A Construct That Only Results from Cognitive Tests "Intelligence is what the test tests." This kind of circular reasoning was offered by Boring in 1923. Colleagues and students say he did not mean to be circular, but rather meant that "IQ" should be solidly grounded in something, and the scores produced by a test were a good anchor. This idea draws heavily on Psychometric Theory. However, as is, it doesn't define intelligence, and doesn't recognize the gap between a concept and measurement of the concept. Think about weight. When you weigh yourself, you might think the result is a measurement of your weight. Actually, the number represents the contraction of the springs in the scale in response to your weight. You don't measure your weight; you measure the effect of your weight on something. However, that effect would be different on different planets or in a swimming pool, and sometimes at different days of the month or times of the day. Think about height. At home, you typically don't measure your height. You stand by the wall, make a mark over your head, and measure the height of the mark from the floor. You measure something that corresponds to your height. It varies by time of day too. Gardner offers that in school, we talk about abstract concepts, about people we'll never meet, about underlying motivations of people from the past that can never be proved…. This has little to do with daily life, he argues, and our ability to assess for a strength at doing this might not really be intelligence, but rather a kind of skill that is useful in a few settings. This might also be why cognitive, achievement, and intelligence tests overlap so much. Take the SATs and GREs for example. If you're interested…. GREs predicted 1st year graduate school grades well, but did not predict beyond 1st year of school. They control 10% of the variance in all graduate evaluation (grades for our years, professor ratings of knowledge, professionalism…). Thus, their real world predictive validity may be rather poor. However, GPAs and recommendation letters don't really tell us much, and undergraduates use GREs to evaluate students (so you need high GRE current students to look good to potential students), and first year grades are part of adjusting successfully to graduate school. 2) Information Processing This idea draws heavily upon Neuropsychology. entails the speed of impulse conduction, the branching of neurons in the brain, the efficiency of glucose metabolism in the brain, decision time… Neisser covers the ideas about this well. He notes that "smarter" people process and use information faster, but different kinds of information are processed differently, so different types of intelligence would depend on the different types of information we could use. High scores reflecting faster reaction and processing times might mean little when there was plenty of time to solve problems, and thus higher IQ wouldn't make a difference in the real world settings (though many disagree and apply processing speed to reading, problem solving, and daily tasks). Even if you don't think of this as being part of "intelligence," Gardner points out that your ability to process visual stimuli (letters), tie it to auditory stimuli (sound), and long-term memory (words) significantly impacts you ability to communicate in verbal and spoken forms. Language is, after all, one of the main ways we learn about our world and store our memories about it. 3) One General Ability and Several Additional Abilities This model has been discussed extensively by many, mainly Spearman, Thorndike, and Thurstone. | |||||

|  | ||||

| |||||

|  | ||||

|  | ||||

| This conceptualization of intelligence is heavily based on Statistics, especially factor analysis. All three, however, acknowledged that non-intellective factors had to go into this somewhere, like motivation, persistence, and conscientiousness. However, the definition of these terms may be culturally and value laden. These views have been combined into hierarchical theories that retain both g and s, like Horn, Cattell, and Carroll, who's ideas will form the basis of some of our interpretations of the WISC IV later this semester. | |||||

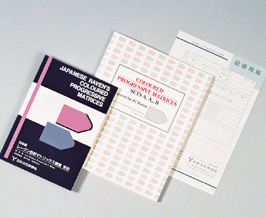

Some tests, like the Raven Progressive Matrices, have been very popular for decades. It requires analyzing about 60 matrices with a missing element, and you have to complete the pattern. |

| ||||

At first, critics thought it was a function of error in the newer IQ tests, and that the Raven's data wouldn't show increases in scores. However, "culture fair" tests like the Raven seem to show even larger gains than the other kinds of tests. | |||||

4) Act Purposefully, Think Rationally, Deal Effectively This is the basis of Wechsler's definition of intelligence. His test allows for both g and s definitions of intelligence, and provides an overall number as well as several smaller numbers representing discreet skills. Others have worked within this model and argued that this fits perfectly with cultural differences, because "deal effectively" varies depending on the culture's definition of important tasks (hunting for food, business savvy, social skills, or personal insight and reflection), and the importance of these tasks (enjoyment vs. survival for example). |  | ||||

Wechsler's model also allows for another distinction seen in discussions of intelligence, that of crystallized and fluid. Who was the 16th president of the US? If you think a second, you'll say "Lincoln." You were not likely thinking of Lincoln before I asked, but could recall it. This is crystallized intelligence, sometimes called Gc (G for general intelligence and c for crystalized). It's heavily based on established knowledge, and cultural and educational opportunities. On the other hand, if I asked what's 15% of $27.30, you won't know it most likely, but can figure it out now. That kind of thinking is fluid intelligence, or the ability to manipulate information on the spot in novel or casual settings to arrive at an answer or decision. This is sometimes called Gf (G for general intelligence, and f for fluid). Interestingly:

Thus, Gf is not the same as Gc, but Gc appears to contributes to Gf. Also interesting, high Gc and Gf people in highly complex jobs maintain high Gf and Gc longer. People with high Gc and Gf in low complex jobs maintain Gc but lose Gf over time. If you are wondering whether IQ scores are stable and actually relate to anything outside of school settings:

The point is that IQ measures something that is related to everyday life, even if it is not exactly what we think. Given your current financial state, you might be more interested in this:

| |||||

5) Multiple Intelligences Gardner is the main proponent of this theory. Gardner believes that there are multiple kinds of intelligence. He also refers to them as basic types of talents, or learning styles for interacting with the world, so he isn't wedded to the traditional term "intelligence." Think of this as there being seven kinds of g or general abilities, and instead of being highly intercorrelated, they are fairly independent and unique. Each marks a potential that environment supports and develops, or devalues and retards, and "gifted" individuals show exceptional promise in these areas, and experts have achieved some mastery of the skill area. |  | ||||

Creativity is creating something new in a specific domain, but a genius is someone who is gifted, achieves mastery status, and revolutionizes the field. Each is common across all cultures and innate to humans and maybe lower life forms too, and there may well be multiple kinds of memory to underlie the experiences each kind of intelligence includes. Gardner notes we often don't realize this because of three errors in our thinking. He calls them "Westist," "Testist," and "Bestist" thinking. Westist values only the logical, rational, abstraction skills a critical scholar is thought to benefit from. Testist views are that if we can't test and score it, it isn't important. Should we be worried about creativity? Well, that depends on whether we can make creativity tests. Finally, Bestist thinking reflects views on what is ultimately right and wrong, and socially valued and accepted as ideal. Gardner's Model of Intelligences

Of course, these different intelligences can interact. A surgeon needs linguistic intelligence to read medical books and understand lectures, spatial intelligence to visualize the human body with nerves and arteries, and kinesthetic intelligence to make precise cuts and scalpel movements. He or she requires some interpersonal intelligence to have an operating room that runs smoothly and effectively, with each person working to the best of their ability and bearing the stress of the work well. It requires intrapersonal intelligence as well, both to handle the stress for oneself, as well as empathize with the patient before surgery to explain the procedure in a sympathetic and comforting way, and after surgery to help them recover. Gardner also gives the example of teaching piano. Some children get better by watching others (interpersonal intelligence), by playing a passage over and over (kinesthetic intelligence), or by focusing on rhythm and musical notation (logical intelligence). This would be why some people show high levels of g on IQ tests and do well in school, but are not "productive" or "successful" in life, and why some people may be very successful and happy in life, but show poor grades and IQ scores. The issue is that IQ tests assessing g probably only assess the first two areas of intelligence. You can guess that Gardner is not big on current assessment techniques, and instead prefers a more complex, multi-disciplinary team approach to assessing children's potential and intelligence. He does support assessment as a process, however, to 1) to help identify weaknesses for correction early on in life, and 2) to help identify strengths in children to know how best to help them understand the world. These two things together could help them choose a career later in life, since you just can't learn everything. The corollary is, of course, that we can't evaluate everything either, and Gardner acknowledges this. I play guitar and piano well enough to know that I play really badly, I sing well enough to know not to do it in public, and I dance well enough to know to only do it in dark crowded bars. Thus, Music and Body-Kinesthetic assessment won't be done in my office. Last, worth noting is that Gardner comments on differences between groups in his theory of intelligence by saying that there may be genetic differences between different groups, but genes likely determine one's potential only. He doesn't think most humans get anywhere near fulfilling their potential, so group differences are more likely noticeable when there are environmental differences. This does not mean that he thinks everyone has the same level of intelligence in these areas, or that everyone has some special area in which they excel. His theory is based on some hard science, and should not be seen as simply a "feel good" theory. | |||||

6) An Aspect of Developmental Steps Piaget offered his ideas about Child Cognitive Development, and many of his stages do correspond to increases in child cognitive test performance. Further, his ideas about children developing one kind of cognitive skills and then building on it in the next phase of development seems to match what others have observed. Of course, he stuck to the idea of stage progression a little rigidly, and we now know children may not move straight through them , or may seem to gain skills from the next stage without having fully mastered the skills from this stage. |

| ||||

7) Other Ideas Snyderman and Rothman did a study in 1988, and asked over 600 professionals what they thought of IQ and intelligence. They offered:

Of note, only 13% rejected the idea of g in favor of models that endorse multiple kinds of intelligences. Others (Samuda) caution that intelligence is not an entity, like a book, or a characteristic, like height, but rather an attribute, like honesty. It varies from situation to situation, and is partially determined by social values and standards. Samuda discusses a study where they bred two strains of rats. One was bred by choosing the smartest rats in the liter for a couple of generations and then letting them breed, another by choosing the dumbest rats in the liter for a couple of generations. Being a "smart" rat was based on reaction times and ability to learn mazes. In the "natural environment" of a maze, the differences were obvious. In the "impoverished environment" of cages with food and water and nothing more, they were almost indistinguishable. In the "enriched environment" with cages with wheels, mazes, toys, etc… they were almost indistinguishable. Samuda is cautioning us to remember that intelligence might not be at all what we've been thinking, but rather a dynamic process between the person and the environment. Ceci also subscribes to this view that intelligence is the result of an interaction between the individual and the environment. Some of his research is extremely interesting, but we're saving it for when we discuss culture and intelligence. | |||||

Before you go on, now is a good time to summarize what you're learned. Below, write a brief explanation for

what you think intelligence is

what are the major debates in the field about intelligence

what problems do you see with having such a complex construct that comes in so many different forms

| |